Driving up the coast to San Francisco a couple of Saturdays ago, I saw a dark geometric formation streak across the sky. I shrieked in delighted surprise when I realized it was a formation of military planes on its way to perform at Fleet Week. I wasn’t expecting to see them so far south of the Golden Gate, but there they were, shooting across the view of my car window. The week before, I stood on the beach watching a similar formation, this time a quartet of stunt kites. Four men on the beach pulled strings and weaved around each other creating an aerial ballet for anyone who looked up and a ground-level dance for strollers passing by. At sunset I stood at the edge of Pier 39 and saw a familiar formation of geese, not quite streaking across the sky like the planes I saw earlier, but in the same geometric shape nonetheless.

Driving up the coast to San Francisco a couple of Saturdays ago, I saw a dark geometric formation streak across the sky. I shrieked in delighted surprise when I realized it was a formation of military planes on its way to perform at Fleet Week. I wasn’t expecting to see them so far south of the Golden Gate, but there they were, shooting across the view of my car window. The week before, I stood on the beach watching a similar formation, this time a quartet of stunt kites. Four men on the beach pulled strings and weaved around each other creating an aerial ballet for anyone who looked up and a ground-level dance for strollers passing by. At sunset I stood at the edge of Pier 39 and saw a familiar formation of geese, not quite streaking across the sky like the planes I saw earlier, but in the same geometric shape nonetheless.

All these mysterious formations evoked a multitude of feelings and memories. Seeing the jets above, I reveled in awe and wonder at the creativity and boldness of the human mind while also dreading and grieving their witness to war. The kites made visible the invisible beauty and grace of wind as they also testified to its destructive power in hurricane and tornado. The flight path of geese, unrehearsed yet perfect, both humbled my sense of human superiority and refashioned me to that one perfect pattern that all creation reflects—Christ the Logos.

Hidden in the patterns and surprises of human achievement and natural creation were signs and reminders that God has fashioned all things to be in right relationship, forming us to be a dance, ordering us out of chaos, transfiguring our weapons of war into plowshares of delight and wonder. The patterns of God’s beauty, God’s creative Word spoken in Christ, are all around us. We need only look, reflect, and remember.

I relearned this lesson with about 200 high school students a couple of weeks before. We sat in the church of St. Lawrence the Martyr in Santa Clara searching for the signs of God’s presence. First we remembered that we were already in the holy presence of God. Then we asked ourselves, “How do we remember that? What reminds us of God’s presence?” This led to a discussion about symbols.

Our daily lives are filled with signs and symbols—birthday cakes and candles, wedding rings and baby’s first shoes, grave markers and memorials. These symbols don’t just remind us of things past but teach us about present things and challenge us to strive for future things hoped for. Because when we speak of symbols, we are not talking about “fake” things, as when we say “it’s just a symbol.” Rather, we are talking about a reality that is so immense that every time we encounter that symbol, we learn something new about ourselves, about our God, and about our relationship with each other and all of God’s creation.

Our worship is filled with symbols. Next time you celebrate Eucharist, seek the more “hidden” symbols—those objects, gestures, people, and places clothed in ordinariness that we often ignore, take for granted, or pass by without thought. Ask yourself: What does this symbol remind me of? What does it teach me about God? What does it teach me about myself as a Christian? What does it challenge me to do so that God’s presence is seen more clearly in my life and in the world?

If we look deeply, enter fully, and reflect prayerfully upon the signs and symbols that surround us, we’ll see that…

Earth’s crammed with heaven,

And every common bush afire with God;

But only he who sees, takes off his shoes,

The rest sit round it and pluck blackberries,

And daub their natural faces unaware….

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh, Book Seven

Three years ago, All Saints Day, I was at San Quentin. I joined their music ministry made up of inmates for their Mass. Some of these men had been there only a few years; others had been there longer than I had been alive. I had gone there a few times before at the invitation of a Franciscan brother to sing for the inmates, and I was confronted by the hidden presence of God in these men. We sang “Blest are They” during Communion, and as their voices filled the small chapel, I was voiceless when we got to the refrain: “Rejoice and be glad! Blessed are you, holy are you. Yours is the kingdom of God.” These men—condemned, put away, forgotten, hated by society, and some ultimately killed by society—are nonetheless loved and blessed by God. God surprises us with his presence not only in delightful things but also in the dark places of human life.

In this week’s DSJ Liturgy Notes, you’ll find:

- Creating a Liturgical Environment: Planting Spring Bulbs

- Upcoming Events and Workshops

- Respect Life: Seeing the Whole Picture

- Respect Life: A Self-Reflection

- Respect Life: Resources for Abolishing the Death Penalty

- A Gift for You: Daylight Savings

- Celiac Sprue Disease – FAQ

- 66.4 Million Catholics

- Seek and Ye Shall Find: Parish Classifieds

- Sample Intercessions for October 24, 2004

This week, look up and look around and search for all the signs that we are in the holy presence of God.

Diana Macalintal

Associate for Liturgy

I am the worst gardener. Over the years, I’ve killed two cacti, a jasmine bush, and several potted plants. But I have had some success with bulbs. A few weekends ago, I planted a few dozen purple and blue hyacinths, anemones, tulips, and crocus. If all goes well, and the squirrels don’t steal them away during the winter, the bulbs should bloom in the spring, right in time for Lent.

I am the worst gardener. Over the years, I’ve killed two cacti, a jasmine bush, and several potted plants. But I have had some success with bulbs. A few weekends ago, I planted a few dozen purple and blue hyacinths, anemones, tulips, and crocus. If all goes well, and the squirrels don’t steal them away during the winter, the bulbs should bloom in the spring, right in time for Lent.

In a similar way, the church’s most vulnerable—the Elect—are fighting their own spring battle. During Lent, the Elect, their godparents, and the church community begin an intense discipline to prepare for the Easter celebration at which the Elect will be baptized. This discipline includes intensified prayer, fasting, and works of charity and justice.

In a similar way, the church’s most vulnerable—the Elect—are fighting their own spring battle. During Lent, the Elect, their godparents, and the church community begin an intense discipline to prepare for the Easter celebration at which the Elect will be baptized. This discipline includes intensified prayer, fasting, and works of charity and justice.

For this reason, the church prays fervently for the Elect in rites called Scrutinies. Through these rites on the third, fourth, and fifth Sundays of Lent, the church prays that God will strengthen the good things that have been growing in the Elect’s faith life and will remove the barriers that keep the Elect from trusting completely in God. During this period, there are also other prayers, blessings, and anointings for the Elect to give them the courage they need to profess their faith in God and make it through to the other side of those baptismal waters.

For this reason, the church prays fervently for the Elect in rites called Scrutinies. Through these rites on the third, fourth, and fifth Sundays of Lent, the church prays that God will strengthen the good things that have been growing in the Elect’s faith life and will remove the barriers that keep the Elect from trusting completely in God. During this period, there are also other prayers, blessings, and anointings for the Elect to give them the courage they need to profess their faith in God and make it through to the other side of those baptismal waters.

There are no tricks in this full bag of treats!

There are no tricks in this full bag of treats!

Because God loves you so much,

Because God loves you so much,

Don't be chicken! You can become a better cantor! Learn the basics that will improve your singing technique and your leadership skills, and practice the habits that will make you a better leader of musical prayer. Some participants will have the opportunity to cantor and receive immediate feedback.

Don't be chicken! You can become a better cantor! Learn the basics that will improve your singing technique and your leadership skills, and practice the habits that will make you a better leader of musical prayer. Some participants will have the opportunity to cantor and receive immediate feedback.

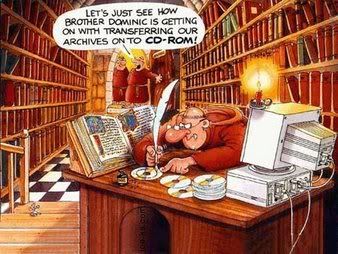

“The Internet causes billions of images to appear on millions of computer monitors around the planet. From this galaxy of sight and sound will the face of Christ emerge and the voice of Christ be heard? For it is only when His face is seen and His voice heard that the world will know the glad tidings of our redemption….Therefore,…I dare to summon the whole Church bravely to cross this new threshold, to put out into the deep of the Net, so that now as in the past the great engagement of the Gospel and culture may show to the world ‘the glory of God on the face of Christ.’” – Pope John Paul II

“The Internet causes billions of images to appear on millions of computer monitors around the planet. From this galaxy of sight and sound will the face of Christ emerge and the voice of Christ be heard? For it is only when His face is seen and His voice heard that the world will know the glad tidings of our redemption….Therefore,…I dare to summon the whole Church bravely to cross this new threshold, to put out into the deep of the Net, so that now as in the past the great engagement of the Gospel and culture may show to the world ‘the glory of God on the face of Christ.’” – Pope John Paul II

Bishop Patrick McGrath and the Associate for Liturgy invite all liturgists and clergy of the diocese to participate in the 3rd annual morning of study and reflection on the Eucharist. This year, Reverend Edward Foley, Capuchin, will guide us through the ministries of preaching and presiding and will give special focus on the Eucharistic Prayer. Fr. Foley is a professor of liturgy and music and the chair of the Department of Word and Worship at the

Bishop Patrick McGrath and the Associate for Liturgy invite all liturgists and clergy of the diocese to participate in the 3rd annual morning of study and reflection on the Eucharist. This year, Reverend Edward Foley, Capuchin, will guide us through the ministries of preaching and presiding and will give special focus on the Eucharistic Prayer. Fr. Foley is a professor of liturgy and music and the chair of the Department of Word and Worship at the  Spend an evening in musical prayer, reflection, formation, and challenge with Reverend Edward Foley, Capuchin, who will guide us through the Rite of Communion, highlighting how our musical choices and habits can serve or hinder the action of the Eucharist. Fr. Foley's presentation will be musical, mystagogical, and meaningful for all who sing the liturgy.

Spend an evening in musical prayer, reflection, formation, and challenge with Reverend Edward Foley, Capuchin, who will guide us through the Rite of Communion, highlighting how our musical choices and habits can serve or hinder the action of the Eucharist. Fr. Foley's presentation will be musical, mystagogical, and meaningful for all who sing the liturgy.

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther, a Catholic Augustinian priest in Germany, nailed to the doors of Wittenberg Castle Church (essentially the bulletin board of this university town) an invitation to discuss and debate the pastoral practices of the church. His 95 theses raised the question of justification (salvation). He argued that if scripture taught that by God’s grace alone are we saved, why then did the church encourage the practice of selling indulgences—certificates that shortened one’s time in purgatory. He argued that salvation is God’s work alone, and no amount of human effort or money could manipulate the mind of God. His argument was solidly Catholic and in line with one of the church’s greatest teachers—St. Augustine. Yet, over the centuries, the church had developed practices, such as private Masses and payment for these Masses to be said for private intentions, that took on the appearance and eventually endorsed that salvation could be bought or bartered. Luther’s action was not meant to divide the church but rather to reform it and remind it of its roots. But in part because of an attitude of defensiveness and a bit of stubbornness on both sides, the church excommunicated Luther and Luther and his supporters condemned many of the church’s teachings and practices. Since then, Lutherans and Catholics have been divided.

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther, a Catholic Augustinian priest in Germany, nailed to the doors of Wittenberg Castle Church (essentially the bulletin board of this university town) an invitation to discuss and debate the pastoral practices of the church. His 95 theses raised the question of justification (salvation). He argued that if scripture taught that by God’s grace alone are we saved, why then did the church encourage the practice of selling indulgences—certificates that shortened one’s time in purgatory. He argued that salvation is God’s work alone, and no amount of human effort or money could manipulate the mind of God. His argument was solidly Catholic and in line with one of the church’s greatest teachers—St. Augustine. Yet, over the centuries, the church had developed practices, such as private Masses and payment for these Masses to be said for private intentions, that took on the appearance and eventually endorsed that salvation could be bought or bartered. Luther’s action was not meant to divide the church but rather to reform it and remind it of its roots. But in part because of an attitude of defensiveness and a bit of stubbornness on both sides, the church excommunicated Luther and Luther and his supporters condemned many of the church’s teachings and practices. Since then, Lutherans and Catholics have been divided.