Liturgy isn't the work of just a few people. Everyone who celebrates the liturgy has a role to play. And the work we do together can change the world. This is the FORMER liturgical newsletter for the Diocese of San Jose. Find some help here to do your work.

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

The #1 thing you can do today to make the world a better place

At the end of the closing ceremonies (which, let's be honest, did not compare even remotely to the opening ceremonies), one of the NBC commentators said about this world-changing spirit of the Olympics: If we can be this way for 16 days, why not three weeks? Why not a month? Why not longer?

I do believe that good Olympics, like good liturgy, gives us a little glimpse of what the Kingdom of God could be like on earth. And once we get a glimpse, we want more.

Continuing that note, ZenHabits has a post about the #1 lifehack (slang for something that improves your life) you can implement today for making the world a better place. It's not written from a religious point of view, but we in the Church can certainly be reminded of how simple it can be to do something today to make the reign of God more visible in our world today.

Friday, March 21, 2008

A Good Friday Reflection

Is there anything beautiful about suffering?

Year after year, for two thousand years, millions of people around the world gather on this day to commemorate the suffering and torture of one man. Why is his pain and agony so attractive to us?

O bleeding head so wounded, reviled and put to scorn.

No comeliness or beauty your wounded face betrays.

Yet angel hosts adore you and tremble as they gaze.

A 12th century mystic named Bernard of Clairvaux wrote those words as he meditated upon the image of the dying face of Christ. What is it about this human, fragile, bloody face that makes even the angels tremble?

On a fall day in October, 2006, I think the angels trembled.

On that day, in a small town named Paradise, Charles Roberts entered an Amish schoolhouse at around 10:00 AM carrying a shotgun, a handgun, wires, chains, nails, and flexible plastic ties which he would use to bind the arms and legs of his hostages. He ordered the hostages to line up against the chalkboard and sent away from the classroom a pregnant woman, three parents with infants, and all 15 male students. The gunman, a father of three children, remained inside the school house with the remaining ten female students. The youngest was six; the oldest was 13.

The first police officers arrived about ten minutes later and attempted to communicate with Charles through the PA system in their cars. Charles ordered the police to pull back, and if they didn’t within two seconds, he would begin firing. They did not comply, and he began shooting.

Charles killed three girls, and then he shot himself. Two more girls died the next morning. The youngest victim was six. The other five girls were in critical condition.

News reports stated that most of the girls were shot “execution-style” in the back of the head. But according to Janice Ballenger, the deputy coroner in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, she counted at least two dozen bullet wounds in one child alone before asking a colleague to continue for her. Inside the school, she said, “there was not one desk, not one chair, in the whole schoolroom that was not splattered with either blood or glass. There were bullet holes everywhere, everywhere.”

There is nothing beautiful about this. Suffering, pain, and death are not God’s will for us, nor was it the Father’s will for his Son, Jesus. Just as on that day on Golgotha, heaven surely must have wept on that morning in Pennsylvania.

The angels wept. But the next part of the story is what made them tremble. What happened next could only have been the will of God, for no human could have done this alone.

Barbie Fisher was one of the girls who survived the massacre. She told the story of how her sister, Marian, the oldest hostage in that school room, had begged Charles to shoot her first so that he might spare the younger girls. So he did. After seeing her sister shot, Barbie asked Charles to shoot her next. She received bullet wounds in her hand, leg, and shoulder.

Two days later, the grandfather of Marian stood in their home with her lifeless body laid on her bed being prepared for her burial. He called over the youngest of his family to come and stand next to Marian. Speaking to all those in the room, he looked intently at the children and told them, “We must not think evil of this man.”

Later that day, a reporter asked this weary, grey-bearded grandfather, “Have you forgiven this man who killed your granddaughter?” He turned his face away from the camera not wanting the attention. “Yes,” he replied. “How can you do that?” the reporter asked. “With God’s help,” he answered.

What made the angels tremble was love—absolute, complete, love.

Here at the cross, we encounter the ultimate revelation of God’s love. It is where God proves that God will do anything for us, even die, no matter what we do, just so he could love us. God takes this instrument of torture and death and turns it into a throne of mercy and grace. God takes defeat and despair and turns it into triumph. God takes the death of one and turns it into life for all.

At the cross, God takes our pain, our desperation, our horror, our hate, our confusion, our fear, places it all onto a cross and transforms it into beauty, truth, and goodness. God takes death and turns it into forgiveness, mercy, and peace.

That grandfather and the Amish community attended the funeral of Charles Roberts who killed five of their own. They took in his widow and their three children into their own families. They helped them pay for Charles’ funeral expenses and have even begun a fund to support the killer’s family now that they are left with no father.

The cross given to that community and their response to it doesn’t make sense, does it? How can something so heinous, something so ugly turn into something so beautiful? Because God is God…and God is Love…and the act of the cross is no longer a matter of reason and logic, but a matter of love.

We who follow Christ do not shy away from the pain and suffering of the world. As Jesus did, we embrace it with open arms. On this day, most especially, when we gather to tell the story of Jesus’ passion and death, we stare it in the face together, we do not look away, and we respond—as best we can, trembling not with human fear and hatred but with the incomprehensible, immense love of God.

Sometimes, try as hard as we might, we can look into the pain and suffering of this world, of our own lives, and not see the beauty. The ugliness can be so unbearable that we can’t see or feel God’s love.

At these moments, it’s so easy to lose hope and despair. But there is another choice.

Maria Thompson is a spiritual director in Seattle who counsels people who are grieving because of death or loss. She describes her work like this: “Standing at death’s door is the most intimate and sacred space to stand. It is an act of being, not an act of doing.” She continues, “I am a person who stands at death’s door; that is my job. I am a person who helps people in the darkness of death find the movement of eternal life. So, I sit on the ash heaps. Patiently. As long as they need me to, that is where I sit.” (from Presence manuscript)

When we face the cross and promise to remain there “in the ash heaps,” no matter how absent God seems, we also enter into a promise with each other—a promise to bear the cross together. For the cross requires relationship.

For Christians, relationship is always the cross—the intersection, the interaction, the giving and taking, the forgiving and sacrifice—between people and between God and God’s people. The cross is a struggle of opposites and differences—but a struggle that gives birth to new life, to new and renewed relationship.

In Jewish tradition, the very act of creation was born out of the relationship between God and Chaos. Listen tomorrow night to the first reading. In the beginning was God, and there with God was nothingness. The union between God—the fullness of all there is—and nothingness gave birth to life, night and day, earth and water, plants and humans. And our whole life through, we are constantly placing before God all of our nothingness and asking God to again make something new out of it.

When Christ was nailed to the cross, what was born out of that union between God and all that was not God was the Church—us—people who look upon death and see life; people who experience pain together and offer in return love.

As offspring then of Christ, our first task is to acknowledge the radical love of God by having the confidence to approach this throne of grace and pray for each other, even if our prayer is only, “My God.”

The Church makes its most intense prayers on this day. Later this afternoon, after hearing again the story of God’s love nailed to the cross, our Bishop will lead us in the Great Intercessions which are prayed only today. These are ten solemn prayers for the world in which we ask God, through supplication and silence, kneeling and raised arms, to take the world’s chaos and re-create it anew. It is the Church’s way of being there, in hope where there’s only despair, in faith when it feels as if death has won.

***

Now you might want to stand back, because I’m not sure if what I’m about to say will cause me to be struck down by lightning.

I don’t like the song, Were You there? I think it’s a lovely song and nice to sing. But every time I hear that opening line—“Were you there when they crucified my Lord?”—all I can say is, “Nope!”

No, I wasn’t there at Golgotha thousands of years ago. No, I didn’t see him nailed to the tree. No, I didn’t see him laid in the tomb.

But I do tremble.

Because I am here in 2007 in San Jose, and God knows there are enough people today being crucified right before our eyes. You only have to turn on your TV, or log onto the Internet, or go to work, or step out your door, or even just wake up in the morning.

There are people right now out there, in here, who are being nailed to trees of depression and abuse, to debt and divorce. We know real people, maybe it’s even you, who are being sealed up in tombs of unemployment, cancer, loneliness, who suffer a slow death because of the inability to forgive or to ask for forgiveness. Our world is still, after four years, being crucified to the cross of war, our Church is still being nailed to a tree of scandal and secrecy, our cities and homes are still being buried by violence, poverty, broken families, and broken hearts.

No, I don’t need to go back to Calvary to be where Jesus is crucified. Calvary is right here, right now.

But so is the resurrection. When any of us take up the cross of Christ, we proclaim our faith in his resurrection.

But what is the cross? What is your cross?

Bishop Kenneth Untener once said that the cross is that to which we say, “Anything, Lord. I’ll do anything…but that.”

That that is the cross. It’s the thing that you can’t imagine doing because you’ve been hurt too much, because you’ve been betrayed, because you’re too angry, because it feels just too good to hang on to bitterness, because you’re too busy, because you’re too scared. “Anything, Lord. I’ll do anything…but that.”

The reason we remember the day Jesus died at the Place of the Skull is because on that cross—on Jesus’ “anything-by-that”—we learn the way to resurrection, because when we embrace Christ and his cross, we never embrace it alone. We embrace the cross together, with this community. It is through individual people that we see up close the body of Christ for ourselves. But it’s through the community—when we gather to tremble at the love of God and offer our meager, imperfect prayers—that we receive strength and faith enough to live as the body of Christ for the world.

It’s hard to follow Christ; it’s hard to embrace the cross. Tomorrow night thousands of people around the world who have decided to follow Christ will stand at the edge of a dark black pool of water, a deep chasm of nothingness, and just before they are submerged into that abyss, they will be asked, “Do you believe in God, in Jesus, in the Spirit?”

I guess it would be pretty easy for them and for us to say “I do.” But if we heard those words for what they really mean, we all might hesitate in our response. Those seemingly-simple questions mean this: “Will you proclaim God’s justice even in the midst of persecution?” “Will you welcome the stranger?” “Will you follow the example of the saints and martyrs who gave their lives for the faith?” “Will you allow yourself to be nailed upon your anything-but-that?”

If we and those preparing to be baptized tomorrow night dare to say, “Yes, I believe,” we really have no choice but to love, but to serve, but to give our all. We have no choice but to give our lives to the poor, the weak, the sinner, the criminal, the adulteress, the tax collector, the unwed mother, the AIDS victim, the drug addict, the homeless man, the coworker who annoys us, the father who abused us, the friend who betrayed us, the stranger who scares us, the person who terrorizes us, the person who is most unlike us.

For on Good Friday, we do not pretend that Christ is not risen. We stand here before the cross and bow low before it precisely because we know and believe that Christ is risen. We venerate this instrument of death, embrace it with trembling hands, and kiss it with timid lips precisely because we believe that the cross is not a dead end, but a sign pointing to God who is the source of our salvation and the community in which God lives.

The Spirit that was breathed upon us from the cross when Jesus commended his spirit into the hands of the Father drives us to turn to each other—to turn to those who are not our mother and take them into our lives as if they were our own. That Spirit of Christ calls us to turn toward those who are not our children and to call them our own beloved. That Spirit of Christ handed over to us moves us to search out those who were the friends of Christ—the sinner, the diseased, the stranger, the outcast—bend down to wash their feet, embrace them and call them friend, and even lay down our very lives for them, our friends.

Behold the Cross on which hung our salvation.

Come, let us adore.

Thursday, December 06, 2007

The Prophetic Ministry of a Church in Transition

Being a monastic community at what I would call the birthplace of 20th century liturgical reform in the US does not keep them immune from the turmoils of the broader church. The monks there are somewhat of a microcosm of the crises the church faces. The number of monks continues to dwindle, even as more men are attracted to their lifestyle. The monks are definitely getting older and frailer (my first summer there, we celebrated the 69th anniversary of priesthood of Fr. Godfrey Diekmann, OSB; although he was bound to a wheelchair, he was as fiesty as I had heard him to be). And the community itself has been rocked by scandal and disappointment.

Through it all, their leader, Abbot John Klassen, OSB, had been, and continues to be, a steadfast, simple voice, calling each member of the community back to hope and faith. In his presentation to the Diocese of San José on December 5, 2007, Tom Zanzig mentioned this address by Abbot John. Just as Tom Zanzig said, it is one of the most powerful statements I have heard a church leader speak publicly.

The statement is from 2005, but it is even more relevant today as we near the end of 2007. And although it is addressed to a particular monastic community, it should be a clarion call, an alarm waking us from our sleep. We are blessed here in the Diocese of San José to feel little of the priest shortage that so much of the rest of our country feels. Yet we are not a church unto itself. We are members of a larger church in transition, whether we feel it or not, like it or not. More is changing in this church of ours than just ordination numbers.

"Remember not the events of the past, the things of long ago consider not; See, I am doing something new!" (Is 43:18-19)

"I suggest that it is our task as a monastery to facilitate the present Church's passing in order to assist in the birthing of the new" (Abbot John Klassen, OSB).

In this Advent season, we prepare for new birth. Listening to the prophets of this season and to the prophets of our day, we would do well, as a church, to look also at what needs to die so that the new birth promised by God may happen.

Read Abbot John's full statement here.

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Giving thanks--"It's not something minor"

Thursday, November 08, 2007

I so want to be in Stephen Colbert's religious education class

***snip***

Keeping with things late night, just on a lighter note, much has been made of the Catholic sensibility as fleshed out by Comedy Central's Stephen Colbert--so much so that there's even a website (and a great one at that) devoted to the "yes-and" approach of the comic's marriage of faith and art.

A religious ed teacher as time allows in his New Jersey parish, during a recent pre-show warm-up with his audience, Colbert talked about his brief stint as Camerlengo...for a conclave of elementary-schoolers.

As questions were being tossed from the crowd, then in the midst of his fleeting presidential bid, the satirist was asked what his first executive order would be.

His answer: "Be kind to each other"... which led to his account of the decree's genesis, reported by an audience member:

[Colbert] didn’t teach Sunday school last year, because he was too busy with the show; but he substituted, and he was subbing on the last day before summer vacation — when the kids didn’t really want to learn anything. And Pope Benedict had just been elected, so they decided to hold a mini papal election.

He and his daughter made a paper-maché miter, with a glitter cross, and then he “very seriously” locked the door, put the key in his pocket, and told the kids, “Okay, nobody leaves here until we elect a Pope.”

They started by making a list of qualities that you should have to be a Pope: ‘knows the Bible’, ‘good person’, etcetera. “And nobody said ‘must be a man’, which made me happy.” Then it came time to vote, but one kid said “Hey, I’m gonna vote for me,” and another said, “I’m gonna vote for me!”, and it looked like trouble.

(Stephen digressed at this point to speculate that all the cardinals probably do this on the first round. “Hey, might as well, who knows, there could be a groundswell…”)

Daughter to the rescue: “Dad, make everyone vote twice.” That way they would all vote for themselves and someone else. The winner was a kid named Gregory (and his daughter had predicted “It’s gonna be Gregory, because he always knows all the answers in class.” Stephen’s daughter sounds like such a cool kid).

So they brought Gregory up to the front, put the miter on his head and the cloth over his shoulder, and said, “Now that you’re the Pope, you need to pick a name; what name are you going to have?”

And the kid goes, “Urban III.” (”He really knows his stuff!”)

What will be his first papal injunction? Gregory holds up his hands (here Stephen holds up his own for a moment, to demonstrate, and then brings the mic back to his mouth), and says, “Be kind to each other.”

At which Stephen went, “All right, that’s it, we’re done, everybody go home!”

...and that's today's word.

***endsnip***

And from Colbert's Knox College commencement speech from 2006, here's some great wisdom about trusting enough to say, "yes." I couldn't help think of young Mary, sitting in her room, going about her own business, not knowing that Gabriel is at her door just about ready to lead her into the greatest improv skit of her life. (My brother does improv. I tell you, it's not easy.) But for us with faith, there is nothing better than to say "yes-and" to all God gives us.

Click the link above to read his entire speech. I laughed through it all.

But you seem nice enough, so I'll try to give you some advice. First of all, when you go to apply for your first job, don't wear these robes. Medieval garb does not instill confidence in future employers—unless you're applying to be a scrivener. And if someone does offer you a job, say yes. You can always quit later. Then at least you'll be one of the unemployed as opposed to one of the never-employed. Nothing looks worse on a resume than nothing.

So, say "yes." In fact, say "yes" as often as you can. When I was starting out in Chicago, doing improvisational theatre with Second City and other places, there was really only one rule I was taught about improv. That was, "yes-and." In this case, "yes-and" is a verb. To "yes-and." I yes-and, you yes-and, he, she or it yes-ands. And yes-anding means that when you go onstage to improvise a scene with no script, you have no idea what's going to happen, maybe with someone you've never met before. To build a scene, you have to accept. To build anything onstage, you have to accept what the other improviser initiates on stage. They say you're doctors—you're doctors. And then, you add to that: We're doctors and we're trapped in an ice cave. That's the "-and." And then hopefully they "yes-and" you back. You have to keep your eyes open when you do this. You have to be aware of what the other performer is offering you, so that you can agree and add to it. And through these agreements, you can improvise a scene or a one-act play. And because, by following each other's lead, neither of you are really in control. It's more of a mutual discovery than a solo adventure. What happens in a scene is often as much a surprise to you as it is to the audience.

Well, you are about to start the greatest improvisation of all. With no script. No idea what's going to happen, often with people and places you have never seen before. And you are not in control. So say "yes." And if you're lucky, you'll find people who will say "yes" back.

Now will saying "yes" get you in trouble at times? Will saying "yes" lead you to doing some foolish things? Yes it will. But don't be afraid to be a fool. Remember, you cannot be both young and wise. Young people who pretend to be wise to the ways of the world are mostly just cynics. Cynicism masquerades as wisdom, but it is the farthest thing from it. Because cynics don't learn anything. Because cynicism is a self-imposed blindness, a rejection of the world because we are afraid it will hurt us or disappoint us. Cynics always say no. But saying "yes" begins things. Saying "yes" is how things grow. Saying "yes" leads to knowledge. "Yes" is for young people. So for as long as you have the strength to, say "yes."

And that's The Word.

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

The Trinity as Football: Now THAT'S Collaboration!

Now I'm not a huge football fanatic (sorry, Mary P-H), but I absolutely love watching great plays.

Then I thought, hey! This play! It's Trinity! I mean, really, as in The Trinity. Seven of the 11 Trinity team members handled the football during that play. They collaborated and cooperated with each other to perform this miracle play. (Read the entire list of players who made this play happen and how they did it.)

We say the Trinity is One (CCC #253). "We do not confess three Gods but one God in three persons."

We say the divine persons of the Trinity are really distinct from one another (CCC #254). The Trinity is One, but the persons are distinct. They aren't different modes of the One God. They are distinct persons, the Son distinct from the Father, and the Spirit bonding them together.

And we say the divine persons of the Trinity are relative to one another (CCC #255). The Trinity is One yet distinct only because they are in relationship. The Trinity acts as one because of their relationship, and outside of this interdependence, there can be no Trinity.

The parallel isn't perfect, and I don't mean to say the Most Holy Trinity is like a football team. But I think we can learn something of the mystery of the Trinity from this amazing sports moment. There was creativity, movement, and dance in this play. Each team member relied on the other, yet in his moment of carrying and throwing the ball, each player was the team. And only by their collaborative, mind-as-one relationship were they able to accomplish something miraculous.

But most importantly--and the reason I think the Trinity matters in our life--is that in witnessing this play, we become a part of it. It doesn't matter that I don't know the intricacies of football or even who the teams are. I was swept up into the amazingness of this moment. In those 62 seconds, I became a fan, the 12th team member. When we experience the amazing union--the deep love--between the Father and the Son joined by the Spirit, we can't help but be caught up in that love as well, pulled into the dance of a great "play." When that happens, our very lives become a reflection of that oneness, that unity, that joy, that love.

And here's why this matters to liturgists. It's in the liturgy that we encounter most fully that intimacy and love of the Trinity. If we can do all we can to prepare liturgies that pull people into that Trinitarian love, into the same kind of excitement and wonder all those fans at that stadium witnessed, we will have helped to prepare liturgies that lead to conversion (yet another football term!).

Okay, okay, I hear all you hard-core theologians and liturgists groaning at the metaphor, and I've taken this simile too far already. Don't take the comparison too seriously. I just thought it was a great, fun football play. :)

Thursday, November 01, 2007

Happy are those who are called to his supper.

I’m pretty sure the “those” are the saints. They are the ones who are already standing around the altar of the Lamb, who already “see him as he is,” as today’s second reading says is our hope. At every Eucharistic prayer, we say that “we join the angels and the saints in proclaiming [God’s] glory” (Eucharistic Prayer II). The saints are where we hope to be, seeing what we hope to see, doing what we hope to do forever.

But sometimes, we think the “those” are us, and rightfully so. Sometimes, presiders even change the words to say “Happy are we who are called to his supper.” Yes, we too have surely been called to the Lamb’s supper, and we respond to that call every time we share in Communion. But this simple change in pronoun misses the point of the supper and the saints and the banquet that we still long for even after we have been filled from the altar table.

Today’s solemnity of All Saints and its assigned readings remind us that the supper of the Lamb is more than the Communion we share on Sunday. The eternal life of the saints in heaven is more than the best day we can think of on earth. The greatest joy, the deepest love, the most wonderful thing we know now cannot even compare to what is awaiting God’s children when what we shall be will be revealed.

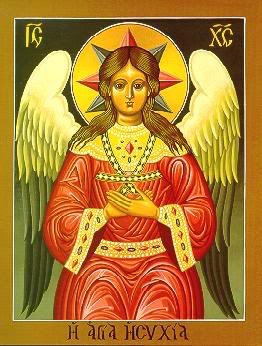

It is good to know that the saints are just like us—everyday ordinary people who lived holy extraordinary lives. But it is also good to remember that the saints point us to something more than the ordinary. Their saintliness makes them more than who we are now. The saints are icons that both reveal mystery and also hide it. They reveal what we are to become—living, breathing signs of the Kingdom on earth. But try as we might, no matter how long we gaze upon the icon, we will never know the full joy of the saints until the Last Day when it is revealed to us by God.

Why does this matter? It matters because we sometimes forget that the promise Christ made to us through his resurrection is real. Sometimes we forget that we are promised “abounding joy” in God’s presence, “the delights at [the Lord’s] right hand forever” (Psalm 16:11). Not just joy but ABOUNDING JOY! Joy overflowing and pressed down until there's just no more room for it, then even more than that! Therefore, no matter what suffering, despair, apathy, or anger that “things aren’t the way they should be,” no matter what, God’s promise is real. Just look at the saints.

But even more so, God’s promise is real even when we think life is pretty good. If you think you’ve got it good now, just wait! It gets even better!

All Saints proclaims God’s faithful promise of “abounding joy.” It’s our day to hope for something more than what we can imagine, to hope for the unimaginable—and to know it's coming. It’s a promise and a hope for all people, no matter what blessings we may revel in or what curses we may be enduring in this moment. For happy, indeed, are those who are called to his supper.

Below is last year's reflection on this joyful day. Happy feast day to all of you!

***

Over the years, I’ve collected several images of saints. It started with a ceramic relief of Saint Cecilia that the members of the Newman Center choir at UCLA gave me as a birthday present. Then a fellow campus minister at Saint Mary’s College in Moraga found a retablo of Saint Librata (also known as Wilgefortis or “holy face”). The legend of this deposed saint (she was removed from the calendar in 1969) tells of her martyrdom on a cross in which she appeared to have the face of Christ. Thus, many of her images show a crucified person with a beard wearing women’s clothing. She is said to be the patron saint of difficult marriages and unwarranted advances by men.

Over the years, I’ve collected several images of saints. It started with a ceramic relief of Saint Cecilia that the members of the Newman Center choir at UCLA gave me as a birthday present. Then a fellow campus minister at Saint Mary’s College in Moraga found a retablo of Saint Librata (also known as Wilgefortis or “holy face”). The legend of this deposed saint (she was removed from the calendar in 1969) tells of her martyrdom on a cross in which she appeared to have the face of Christ. Thus, many of her images show a crucified person with a beard wearing women’s clothing. She is said to be the patron saint of difficult marriages and unwarranted advances by men. But one of my favorite retablos is one I found years ago at the Religious Education Congress, of all places! It’s a small image of a man with a halo walking—more like marching—with a look of determination. Behold, Saint Expeditus, patron of urgent situations, emergencies, and procrastinators!

But one of my favorite retablos is one I found years ago at the Religious Education Congress, of all places! It’s a small image of a man with a halo walking—more like marching—with a look of determination. Behold, Saint Expeditus, patron of urgent situations, emergencies, and procrastinators!All this time, I thought he was a made-up saint. But he’s not! He has a novena, and his feast day is April 19 (four days after Tax Day), but as his fans say, you can celebrate Saint Expy day whenever you get around to it.

The saints indeed know all about our lives and can be models for us on how to deal with the troubles we face each day. Yet the saints really aren’t distant onlookers. They’re here among us. We don’t so much pray to them as we pray with them.

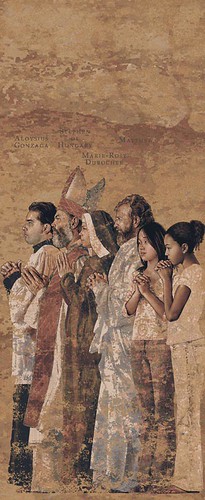

One of the most striking things about the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles is the way the saints face. They aren’t looking at you; they’re standing with you, joining you in prayer around the altar. It’s a beautiful image of what it means to be part of the communion of saints.

One of the most striking things about the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles is the way the saints face. They aren’t looking at you; they’re standing with you, joining you in prayer around the altar. It’s a beautiful image of what it means to be part of the communion of saints.The Catechism of the Catholic Church (948) speaks of two aspects of the communion of saints which it sums up in the Eastern liturgy’s invitation to Communion: “Holy gifts for holy people!” The communion of saints is first a sharing of the good things God gives us, the most wonderful of which is Eucharist. Thus the tapestries at Los Angeles’ Cathedral show the saints standing with us at the altar. Being part of the communion of saints also means that we are united—in communion—with all the living and the dead, all God’s holy people.

That sharing and that communion come together at the altar—the tomb—of the model after which all the saints are formed: Christ. The cult of saints began in the early church when Christians were being persecuted and killed for their faith. Christians would recall their example of faith, often celebrating Eucharist on the anniversary of their death. Their burial places were holy sites where “heaven is joined to earth”—where death in Christ was wedded to eternal life in heaven. These sites were thought to be where one could receive some of the grace of the saint (sharing in the good things of God). Therefore, stone slabs were sometimes placed on top of the martyrs’ graves so the pilgrims could celebrate Mass there. These graves eventually became pilgrimage destinations around which monasteries, chapels, and religious houses were built. (Ever wondered why relics are embedded in the altar?)

Saints model for us how to live because saints show us how to die—die to selfishness and self-preservation; to worrying that you won’t have enough and to worrying that you aren’t good enough; to harboring grudges and withholding forgiveness; to apathy and to waiting until tomorrow to do what needs to be done today—saying “I love you,” “I’m sorry,” “I forgive you.”

They are called saints because in some way they stood apart from the rest of world and showed us how to be counter to what was expected, especially in times of trial.

The poor family who doesn’t have enough food to feed themselves yet welcomes in the stranger with open arms and the best of their kitchen stands apart from those who have more than enough yet have no joy around their table. Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of heaven.

Those Amish who forgave their children’s murderer, attended his funeral, and vowed to support his widow and their children stood apart from what most of the rest of us would have done. Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy.

Those prophets of faithful dissent who speak out against injustice—even injustice in the Church—and are condemned for it stand apart from our “don’t rock the boat” and “keep your head down” indifference. Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you and utter every kind of evil against you falsely because of me. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward will be great in heaven.

The saints stand apart, yet they do not stand alone. All the holy ones of God—you and me and the saints—stand together, dying to ourselves and rising to holiness, sharing in the good things of God.

But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have become near by the blood of Christ. For he is our peace, he who made both one and broke down the dividing wall of enmity, through his flesh, abolishing the law with its commandments and legal claims, that he might create in himself one new person in place of the two, thus establishing peace, and might reconcile both with God, in one body, through the cross, putting that enmity to death by it. He came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near, for through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father. So then you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the holy ones and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the capstone. Through him the whole structure is held together and grows into a temple sacred in the Lord; in him you also are being built together into a dwelling place of God in the Spirit. (Ephesians 2:13-22)

Friday, February 09, 2007

Fr. Thomas Jones, CSP - Lessons Learned and Treasures Received

Fr. Tom Jones, CSP, was my first and best boss in the world of church ministry. When I was a freshman ending my first year of college at UCLA, he and the music director of the University Catholic Center (Newman Center) interviewed me for the position of assistant music director. Part of the interview included leading a mock choir rehearsal with the two of them, teaching them the different choral parts of a song. That was my first clue that this was not your average priest. You mean you’re a priest who sings and reads music and can sing your part against another person? Wow!

Fr. Tom Jones, CSP, was my first and best boss in the world of church ministry. When I was a freshman ending my first year of college at UCLA, he and the music director of the University Catholic Center (Newman Center) interviewed me for the position of assistant music director. Part of the interview included leading a mock choir rehearsal with the two of them, teaching them the different choral parts of a song. That was my first clue that this was not your average priest. You mean you’re a priest who sings and reads music and can sing your part against another person? Wow!In fact, he had already had a long musical life, playing trombone for the marching band of the University of Minnesota. At that time, I had never met anyone from Meen-uh-SOH-tuh, as Fr. Tom would say it. Again, little did I know that years later, I would make my way to his home state, a foreign land for a California girl, to spend six summers studying liturgy.

There was much I didn’t know when I met Tom, or “TJ” as all the students called him, but over the next four years, he formed me into so much of the minister I am today. He was the first homilist who made me cry...in a good way. His homilies were real and so human. After 18 years of going to church, I didn’t know that homilies could be that way. Later, I’d realize that they are supposed to be that way, supposed to “interpret peoples’ lives” through the Scripture (Fulfilled in Your Hearing, 52). Fr. Tom’s homilies always used the events of our lives to show us where God was hidden among the muck and mire, the joys and surprises of each day.

Yet they were never “fluff” homilies, touchy-feely things without substance. He did his work, and like those who have mastered their craft, it never looked like work. Years after I left the Newman Center, I prepared my first reflection for a parish liturgy. I sent Tom my final draft and asked him his opinion. He nicely and genuinely encouraged me, as he always did, but he also told me don’t skip the exegesis. It has to be there, but it doesn’t have to bang you over the head either.

He was the first to correct and discipline me for a serious mistake I made in my job. For me, a perfectionist, making a mistake is horrifying. And being called into his office for “a talk” was petrifying. I had overslept and missed the first half of the 8:30a Sunday Mass at the Newman Center (okay, 8:30a may not be early for you, but it sure is for me!). He called me in the very next day and made it clear to me, in a very gentle but firm way, that this was unacceptable and it was not to ever happen again. I can tell you that I still have nightmares of missing an early morning Mass, but I can also tell you that I have never overslept for Mass since.

Tom, and the rest of the Paulists that I worked with at the Newman Center, were the first priests I met who really, absolutely down to their core, loved the liturgy, and loved the assembly even more. They gathered students, cling-ons (graduates who wouldn’t leave), and villagers (locals who preferred the Newman Center to their parishes) to prepare, discuss, evaluate, and plan the liturgies and the seasons so that the assembly would be fully, consciously, and actively participating. Tom told me to read the documents, read the documents, and re-read the documents again. He sent me to conferences and conventions, institutes and workshops. He gave me opportunities no average pastor would give a 20-year-old. He asked me my opinions and paid attention to my suggestions. And when I eventually became the music director, budding liturgist, and catechumenate coordinator, he followed my directions, took risks, tried new things, and helped me make them better for next time.

We weren’t really close friends like he was with others at the Center, but we understood each other and respected each other, and that was what I wanted and needed from him. It all clicked for me one day when the staff took an enneagram test and we discovered we were both 3s—achievers, needing to succeed, eagles soaring above not just to be admired but also to see the bigger picture. Among all the staff members and student leaders that we worked with over the years, he and I were the only 3s.

Where he could never succeed was with his health. He had always been sick, going through kidney failure, broken legs, two kidney transplants, and skin cancer. For him who refereed ice hockey in his spare time (yes, a little bit of Minnesota in California), this was devastating. But all through it, he was our fearless leader and vision guy, inspiring us to believe in our dreams and showing us the real, concrete steps for making them happen.

He had courage not only in facing his sickness but also in standing up when others would rather keep their heads down. He dreamed big, said the hard words, and gave voice to the vision. He made me believe that what I do matters, not because God is watching or because my soul needs to be saved, but because the impossible vision of the Gospel needs to become a reality in the real lives of the people around us. He taught me that standing up for that vision is not just a bold thing to do; it was the only thing to do if we dared to profess our faith.

Some of you may have seen me wear a small jeweled circle on the lapel of my suit coat. That was from Fr. Tom, his first Christmas gift to me when I joined the Newman Center staff. It’s one of the few pieces of jewelry that I love because it’s so spare yet elegant. Unlike Fr. Tom’s homilies which were verbal jewels, elegant and economical in their use of words, I have rambled on. But I wanted to share with you a little about the person who I learned too late was a mentor in ministry and in life. A friend passed on to me this Holy Thursday homily by Fr. Tom (pdf) from 2005, one year before he would be diagnosed with the cancer that eventually killed him on January 16, 2007, at the age of 51. Although I can’t get Tom’s permission, I think he’d be happy to share it with you, another jewel to offer the church and one last lesson taught and hopefully learned.

Fr. Tom kept a blog during his last several months to keep in touch with his parishioners and his friends. If you'd like to learn more about Tom, click here.

Thursday, March 24, 2005

Triduum 2005

As I drove home last night, I saw what I call the “Easter-is-coming-soon-moon”—the first full moon after the spring equinox. This is the moon that each year determines the date of Easter Sunday which falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox.

I’ve always loved this about the Catholic Church. Our time and the way we move through time are guided not just by our human-made inventions of calendars, clocks, and PDAs, but also by the passing of seasons and the movement of the cosmos. In wonderful Catholic fashion, even our time is both/and: solar and lunar, constant and moveable, made by human hands and God-given. Every act of worship is always first a response in obedience to God’s call. The call to worship is not commanded by our day timer, like an appointment on our “to do” list. It is our response to God who created time by separating the light from the darkness and placing lights in the dome to mark the fixed times, the days, and the years (Gn 1:14). To worship God is to submit our control of time to the one to whom all time belongs. To worship is to submit ourselves to relationship with God and with what God has created.

When the sun sets tonight, the Church will again respond to God’s call. In the annual celebration of the Triduum, we spend three days, 72 hours in worship. Yet the time beginning tonight until sundown on Sunday is both timeless and filled with all of time. It is the ultimate experience of God’s time, kairos, that we can have in this earthly life.

The entire Church watches for the signs of God’s call—the tumult of spring rain, the yellow bursts of daffodils, the greening of trees, the equilibrium between light and dark, the fullness of the moon, and the setting of the sun. If our Lenten watchfulness has taught us anything, we will pay attention to the signs all around us.

During this Triduum, we are confronted with God’s paradoxical signs. We are shown an example of radical friendship by our God washing dirty, calloused, sinful feet. We kiss the sign—the cross—that marks us and claims us at the beginning and the end and throughout our Christian life. We tell again the long history of signs that have led God’s people through the history of salvation: evening and morning, angels and rams, pillars of clouds and walls of water, rain and snow from heaven, seeds and bread for a hungry people, and an empty tomb and a profound command for a desperate world—Go and tell his disciples, he is risen! We wash, anoint, clothe, and feed the Elect now called Neophytes, the living signs of “he-is-risen!” among us. And finally, we ourselves become signs, human yet divine, sinners yet saints, of God’s everlasting promise.

This past week, our nation has been talking a lot about signs. A teenage boy opens fire at his school in Minnesota, killing 10 people, including his grandfather. The New York Times headline today reads, “Signs of Danger Were Missed in a Troubled Teenager's Life.” Advocates on both sides of the issue in Terri Schiavo’s case are watching closely for signs of conscious life in this woman’s depleted body. The signs of our times are calling us to respond.

In this week’s DSJ Liturgy Notes, you’ll find:

- 14 Questions on the Paschal Triduum

- Rite for Receiving the Holy Oils

- Special Intercession for Good Friday

- Disposing of Old Paschal Candles

- Disposing of Old Holy Oils

- The Easter and Pentecost Sequences

- Prayer Over Water Already Blessed

- Vino & Vespers – April 22, 2005

- Special Intercession for April 23/24

- Liberation Theology in Latin America: The Salvadoran Story

- Writings of Archbishop Oscar Romero

- Stations of the Cross/Via Crucis of Oscar Romero

- Diocese of St. Petersburg's Statement on Terri Schiavo

- Classifieds: Seek and Ye Shall Find

Come, let us worship!

Diana Macalintal

Associate for Liturgy

Monday, March 21, 2005

Liberation theology in Latin America: The Salvadoran Story

First year student of the Institute for Leadership in Ministry (ILM)

Editor's note: The following was a paper written for one of Rosa's classes in the ILM. She generously shares with us her insights from her class as well as personal experience as a Salvadoran on the 25th anniversary of the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero, March 24, 2005.

In this paper I will talk about what liberation theology is, how it originated and how El Salvador is an example of liberation theology at work. Particularly, how Monsignor Romero’s life experience and conversion intertwine in the development of the liberation theology that emerged out of the struggle and suffering of the peoples of El Salvador. I will also explain the three-step critical analysis that is necessary to determine if liberation theology is present. And how in light of the Scriptures do we discern and are compelled to change the repressive structures that give birth to the situation. In Spanish we call this process: ver, juzgar, y actuar (see, judge, act).

Elizabeth E. Johnson, a leading theologian of our era defines liberation theology as a “new way of doing theology, one which draws on the experience of systematically oppressed and suffering peoples.” In her book, Consider Jesus, she explains that liberation theology originated in Latin America after the Second Vatican Council. She goes on to explain that this theology can be recognized where there is suffering of a particular group of people, and even though it is closely related to oppression, it shows up differently, i.e., poverty, political disenfranchisement, patriarchy, apartheid, etc. In other words, not all liberation theology is the same. It emerges when community is formed; people come together in faith, become aware of their situation, pray, study the Scriptures and in light of the Scriptures are compelled to seek action to change their situation for the better. “The reflexion of liberation theology is intrinsically intertwined with what is called praxis, or critical action done reflectively.” In other words, to do liberation theology, one must act on behalf of justice.

The first step in the critical analysis is that we must recognize if a situation is really oppressive, name it a sin—not only individual but a collective sin—and consider its root causes. In the case of El Salvador, Monsignor Romero started by asking: Is it God’s will that so many people are deprived of their livelihood? That they are malnourished? That children die, that there is no adequate education, no medical benefits, no shelter and thus, children are thrown into prostitution and abuse? The answers became clear, extreme poverty, political disenfranchisement, and the teaching of the church contributed to their suffering. Obviously this is wrong; the question is why. What came up to light was the fact that a few people owned the land—14 families produce the coffee, cotton and control the export of the products. They called the shots—from backing up presidents that sought only after their own needs, to the flow of money to industry and everything else; in summary, controlled the economy, the government, the police, and the armed forces thus there was no opportunity for anyone else to prosper, or speak up.

Out this oppressive situation, Liberation theology emerged. The majority of Salvadorans came together in faith, became conscious of their own situation, prayed, studied the Scriptures, and listened to the voice of the one who became their leader, Monsignor Romero, not a willing leader at first, but being forced to see the reality of his people, began to act, to shine light on the many injustices committed against the Salvadorean people. He began to use the pulpit to preach powerful homilies, to voice the concerns of the suffering peoples, and to denounce the crimes against those who dare threaten the status quo. His homilies were heard throughout El Salvador:

The day when all of us Salvadoreans escape from that heap of less-human conditions and as persons and a nation live in more-human conditions, not only of merely economic development, but of the kind that lifts us up to faith, to adoration for only one God, that day we will know our people’s real development.

Community as never seen before gathered in search for answers. A radical search for better structures followed, but not without taking its toll. Many, many died in that quest. Many of my friends with whom I went to the University were killed during demonstrations; many became widows and much poverty ensued. However, out of this interaction the true meaning of faith arose.

The second step in the critical analysis is to look whether Christian tradition has contributed to the situation. Questions such as what elements of our tradition have lent themselves or contributed to the problem? Where is the complicity of the church and its preaching? How has Christ been understood in a way that is helpful to the oppressor?

According to Johnson’s methodology, a critical analysis of the role the church played in this situation shows that the tradition of Christology has supported this situation of injustice, and I’m afraid it continues to date. For instance Johnson points out, mysticism of the dead Christ in Latin American piety, symbolized in graphic crucifixes and in Holy Week processions in which the dead Christ is carried and pious folks mourn as if he had just died. This is coupled with a spiritual identification with Christ as a model. Emphasis on the dead Christ works to legitimize suffering as the will of God. It is taught that Jesus Christ suffered quietly and passively; he went to the cross like a sheep to the slaughter and opened not his mouth. The outcome is clear: to be a good Christian one should suffer quietly; one should go to the cross and not open one’s mouth; one should bear one’s cross in this world and, after death, God will give us our eternal reward. “When embraced in a situation of injustice, this pattern of piety promotes acceptance of the status of victim, and anyone who dares challenge their suffering would be seen to go against the example of Christ. It obviously works to the advantage of the oppressor.”

Another difficulty identified in the tradition is the glorification of the imperial Christ—in heaven the risen Christ rules. It’s preached that he sets up on earth human authorities to rule in his name, both in the civil and ecclesiastical spheres. Human authorities represent Christ and are to be obeyed as one would obey him. What happens here is that in an unjust situation this puts Christ in the same group with the dominating powers, and anyone who challenges either authority is disobeying the will of God. This is painful to see and hear. I remember when Monsignor Romero himself followed this tradition and sited with the rich. He was seen as one of the “establishment” of the ruling class. I also remember hearing my own father making statements such as: You can pray all you want, but there will not be priests in this house! You cannot go to church, it’s too dangerous, besides the priests are told what to bless and so it is done! Don’t break any rules, don’t talk outside of this house, you never know who is listening. His statements were typical of the situation we were living—a police state—and they were commonly heard by all of us students and the general population. They were a product of the fear and oppression that invaded our lives. I for one was torn between the extremes. I could see my father’s conservative point of view and the threat to “our way of life,” on the other hand, I could hear the clamor of the people, and much more as a Law students.

The third step comes about, Johnson states, when we read the Scriptures from the perspective of the poor, it makes it very clear that Jesus is on the side of the downtrodden and calls oppressors to conversion. A key text is the scene in Luke where, at the beginning of his ministry, Jesus goes to his home synagogue in Nazareth and reads from the scroll of Isaiah.

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to preach the good news to the poor; he has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord.Sitting down, Jesus says, “Today this scripture is being fulfilled in your hearing” (Lk 4:16-21). This prophecy sets the agenda for Jesus’ ministry, as we see from everything that follows in the gospels. His preaching that the reign of God is near; his singling out the poor and those who hunger after justice for beatitude; the way he feeds and heals and welcomes outcasts—all of this reveals a choice, a preference for those who have not. This is God’s agenda for the poor: that they be released and set at liberty from grinding poverty and oppression. This is good news for the victims. It means that their present situation is not the last word about their lives, but that God has another design in mind. Touching structures as well as hearts, God is opening up a new future for the poor.

The message is clear; Jesus die for us so that we could be free. We ought not to be fixed on the cross but set our eyes on the resurrection. He came to transform us from poor oppressed people into free individuals capable of thinking, working and having the right to earn a decent living. Jesus was not a passive victim. His death came about as a result of a very active ministry in which love and compassion for the dispossessed led him into conflict with the powerful.

And so is the example of Monsignor Romero’s life to the Salvadoran people. At first, he adhered to the traditional teachings of the church and did not want to create any waves; however, he was forced to look at the situation when Fr. Rutilio Grande who was not in agreement with him, was assassinated because he was helping the poor, the heads of the unions who were working to bring about change for a more humane treatment and payment of the factory workers. These workers who daring to question the oppressors, were persecuted and killed by the “mano blanca” or death squads. Monsignor Romero was forced to see that to continue to do nothing was in fact endorsing the behavior of the ruling class. His voice became more powerful, more determined.

When we struggle for human rights, for freedom, for dignity. When we feel that it is a ministry of the church to concern itself for those who are hungry, for those who are deprived, we are not departing from God’s promise. He comes to free us from sin, and the church knows that sin’s consequences are all such injustices and abuses. The church knows it is saving the world when it undertakes to speak also of such things.Monsignor made the Scriptures come alive; his voice could not be denied, and to his demise, he became a real threat to the status quo. Shortly after, he was killed while saying mass.

Here are more examples of his homilies that show his transformation and conversion and became powerful revolutionary thought calling for change and conversion for all of us. What it points out is that one must not be silent when there is oppression and suffering of the people of Our Lord. Monsignor Romero was forced, as I am right here to see what was/is the problem of the people in my country, how the church/preaching contributed to their plight, and finally, looking at this experience, what in the tradition of Christology was overlooked and, in light of the experience of the poor, might be used to shape a Christology that can liberate. It is sad to see, however, that the situation continues and it might have gone back to the same causes. Further, the current Bishop is a Spaniard who does not seem to share the same interest for the good of the people of El Salvador. Again, the situation seems to be a time bomb. It is calling us again to go back, to remember that we are each others keeper and that we must speak for those who cannot speak for themselves.

Tuesday, February 08, 2005

5th Week in Ordinary Time

I confess: I am a makeover junkie. I have seen almost every episode of Trading Spaces, What Not to Wear, and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Now before you hand me my penance for my addiction, there’s something I’ve noticed about these makeover shows. These are not your typical shows in which a person is put under the knife to undergo thousands of dollars of unnecessary plastic surgery in order to feel better and in the end finally realize that it really wasn’t worth it. What has moved me to embarrassed weepiness when I watch these shows is seeing a person be really transformed, not because of new clothes, makeup, a fancy hairdo, perfectly-shaped eyebrows (although that's important), a renovated kitchen, or cool hair product. The transformation happens simply because people—friends and strangers alike—get together to do something for another person so that they could live with more dignity, joy, and peace. Take for instance two of my new favorites: Extreme Makeover: Home Edition and Town Haul.

I confess: I am a makeover junkie. I have seen almost every episode of Trading Spaces, What Not to Wear, and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Now before you hand me my penance for my addiction, there’s something I’ve noticed about these makeover shows. These are not your typical shows in which a person is put under the knife to undergo thousands of dollars of unnecessary plastic surgery in order to feel better and in the end finally realize that it really wasn’t worth it. What has moved me to embarrassed weepiness when I watch these shows is seeing a person be really transformed, not because of new clothes, makeup, a fancy hairdo, perfectly-shaped eyebrows (although that's important), a renovated kitchen, or cool hair product. The transformation happens simply because people—friends and strangers alike—get together to do something for another person so that they could live with more dignity, joy, and peace. Take for instance two of my new favorites: Extreme Makeover: Home Edition and Town Haul.

In Extreme Makeover: Home Edition (not to be confused with Extreme Makeover: plastic surgery massacre), a struggling family is chosen to be given a completely new home, built on their home’s existing lot. A team of carpenters, designers, plumbers, and electricians meet with the family, not to show them designs and plans but just to get to know their story. They play with the kids, look at family photos, hear about their work, learn their hobbies, and listen to their fears for the future. Then they send the family on retreat at a spa or vacation resort to be pampered while the team builds their new home. Throughout the week, local businesses come and donate supplies and services, local artisans create beautiful woodwork, stone paths, and paintings for the new home, and neighbors, classmates, friends, and relatives help paint and hammer, sometimes creating video greetings from far away friends for the family’s homecoming. The big "reveal" is filled with many tears of joy and appreciation from the family and all those who built their home.

In Town Haul, an entire town commits to rebuilding and renovating the homes, businesses, and lives of some of its own members. In one episode, one local affectionately called “Cowboy Bob” was given a completely new home. Bob and his dog live in the outskirts of town in a small cottage. He lost the use of his legs, does not drive a car, and gets around only by electric scooter. The town decided they wanted Bob to have a home in town so it would be easier for him to get to the grocery store and other places he needs to go. The town banded together to form teams: those handy with carpentry and construction work built the foundation and put up the walls; the teens painted the house; the elders sewed pillows, curtains, and bed linens; the local artisans paved a new driveway using stone carving skills they learned in Italy, the Boy Scouts built a new dog house, the town mechanic put together a new scooter for Bob.

Cowboy Bob came home, and standing along his driveway were people he knew and many more he’d never met. The transformation was evident, not in the walls or the wood, but in the hearts of everyone there. Yes, he had a new home, but more importantly, the town had a new vision of relationship in which lives are changed for the better because people work together to make it happen. In a way, the town itself was renovated and became a new home for everyone who lived there. Really, they didn’t do anything extraordinary. They simply used the skills they had, tried to learn some new ones, gave their time and attention to each other, and shared their stories. By their work and care for each other, they changed Bob’s life, but they also changed their own.

I see the sacred season of Lent in the same way. In our town called Church, we have chosen the Elect to be our focus of attention. We build for them a new home not by relegating the task to a few people (pastor, godparents, or initiation directors), but by engaging the whole town in the work. We each do our part, whether it's praying more fervently, fasting more joyfully, or giving what we have to those in need—nothing extravagant, but all ordinary actions that take on extraordinary power when we all do it together. In the end, the Elect are changed into the Body of Christ not simply because we make them over with new clothes of white or new lighting for their mantles. They are changed because they have seen and heard and known the power of God’s love in us--the power to sacrifice in big and small ways, to love our enemies and forgive those who have hurt us, to share bits of bread and wine and call it a feast, and to put another’s needs before our own.

Lent is our extreme makeover. May the practices we take on during this season not be as short-lived as a Botox injection but transform us in our deepest corners of our selves so that our lives become living signs of Christ, dead and risen.

In this edition of DSJ Liturgy Notes, you’ll find:

- Ashes to Ashes: How Our Symbols Speak

- Five More Lenten Symbols

- What Lent Sounds Like

- Lenten Reflections Through Art

- Removing Holy Water from the Baptismal Font During Lent

- Schedule for Rite of Election

- Singers: We Need You!

- Rite of Election Music (listen to the actual music here!)

- Burying the Alleluia

- Flower Arranging Workshop – March 1

- Reverence: Revealing the Presence of God

- Three Ways to Grow in Reverence

- Eucharist: Many Ways to Describe One Mission

May our lenten spring cleaning bring us to new life!

Diana Macalintal

Associate for Liturgy

FILED UNDER: OPENING ARTICLES

The Writing of the Torah

Liturgy Team members at St. Julie Billiart, San José

On Sunday, January 23rd at 3:00 PM, my wife, Diane, and I attended an Open House at Congregation Shir Hadash in Los Gatos. The theme of the Open House was the Mitzvah (commandment) of writing a Torah scroll. This is the fulfillment of the final commandment of the Torah. Congregation Shir Hadash is a community of approximately 550 families that is celebrating their 25th Anniversary.

We were greeted by Rabbi Melanie Aron, who gave us a brief history of Congregation Shir Hadash and who explained the agenda for the Open House. The agenda was in three parts – the Jewish calendar, the Writing of the Torah, and the Holocaust Torah. We were then divided into three groups, with each group attending one of the agenda items. We began in the sanctuary with the Jewish calendar.

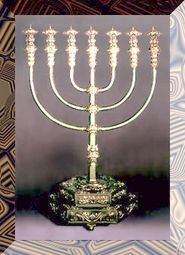

Dianne Portnoy conducted this session on the Jewish calendar. Dianne first explained the significance of the Menorahs in the temple sanctuary. These were seven branch menorahs not the nine branch menorahs that we are more familiar with during the celebration of Hanukkah. The seven branch menorah represents the six days of creation and the day of rest. Dianne then gave a brief description of the Torah. The Torah is the first five books of the bible, written by Moses. Unlike our bible which is produced by printing presses, the Torah must be hand copied from the previous Torah.

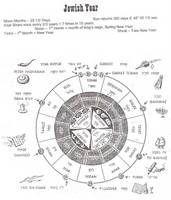

Dianne Portnoy conducted this session on the Jewish calendar. Dianne first explained the significance of the Menorahs in the temple sanctuary. These were seven branch menorahs not the nine branch menorahs that we are more familiar with during the celebration of Hanukkah. The seven branch menorah represents the six days of creation and the day of rest. Dianne then gave a brief description of the Torah. The Torah is the first five books of the bible, written by Moses. Unlike our bible which is produced by printing presses, the Torah must be hand copied from the previous Torah.  The significance here is that all Torahs are identical going back to the original Torah of Moses. Next, Dianne described the Jewish calendar. The Jewish faith celebrates many more high holy days than the Christian faith. All of these high holy days are described in the Torah along with when they are to be celebrated. The Jewish calendar is primarily lunar but with some solar influences. A copy of this year’s Jewish calendar is to the right of this article. We then proceeded to the library for the second part of the agenda, the writing of the Torah.

The significance here is that all Torahs are identical going back to the original Torah of Moses. Next, Dianne described the Jewish calendar. The Jewish faith celebrates many more high holy days than the Christian faith. All of these high holy days are described in the Torah along with when they are to be celebrated. The Jewish calendar is primarily lunar but with some solar influences. A copy of this year’s Jewish calendar is to the right of this article. We then proceeded to the library for the second part of the agenda, the writing of the Torah.We were greeted by Rabbi Moshe Druin, a sofer or official scribe, who lives in Florida and travels all over the world writing new Torahs. A sofer or scribe goes through very extensive and difficult training. Even then not all succeed in becoming a scribe. Rabbi Druin explained that special parchment and ink must be used in creating a Torah. As was mentioned earlier, it must be an exact copy of the previous Torah scroll. Nothing can be added, such as the scribe’s name or date of creation, and nothing can be deleted. The entire community takes part in writing the scroll and it takes approximately one year to complete. Rabbi Druin also explained that as a scroll ages with time and use, parts will eventually be damaged. These parts can and must be repaired. When a scroll reaches a point where it can no longer be repaired, it must be buried. We then proceeded to the school for the third part of the agenda, the Holocaust Torah.

Helayne Green conducted this most unforgettable session. Helayne was part of a group that traveled to Auschwitz in Poland to commemorate the liberation of the prison camp by the Russians. They also took part in the March of the Living where they walked along the railroad tracks from Auschwitz prison camp to nearby Birkenau just as the prisoners did during World War II. The day before they were to fly to Israel, a few of the students found two Torah scrolls in an old bookstore, which they immediately purchased. Fortunately they were able to get them out of Poland to Israel the next day. They were authenticated in Israel to have been written sometime in the early 1920’s. Somehow they survived the Holocaust although badly damaged. The scrolls ended their journey in San Diego, where one remains today. The other was obtained by Congregation Shir Hadash, where it will be restored. Approximately 40% of the scroll was damaged and will be repaired at a cost of approximately $15,000 over a six month period. We were actually allowed to touch it. Helayne also told us that anti-Semitism is on the rise again in Europe.

After that there was a reception and refreshments. We were able to talk with Rabbi Melanie Aron and many of her congregation. The exchange of information and sincere interest was overwhelming. Just as at St. Julie’s, where All are Welcome, so it was also at Congregation Shir Hadash. We thank Rabbi Melanie Aron and Congregation Shir Hadash for their hospitality and the opportunity to experience such a moving interfaith event. It was a wonderful educational experience and we both hope to be able to attend more of these types of interfaith events.

Monday, January 03, 2005

Week of Epiphany

My father lived most of his life on a beach. Once I visited his hometown in the Philippines and climbed up a ladder into a small beach hut on stilts made of bamboo shoots and banana leaves where a cousin I just met taught me to play chess. Every day my father and my brother would wade out into the ocean, and I would watch from the hut, never once venturing out into the water even though the days were mild and the ocean calm.

My father lived most of his life on a beach. Once I visited his hometown in the Philippines and climbed up a ladder into a small beach hut on stilts made of bamboo shoots and banana leaves where a cousin I just met taught me to play chess. Every day my father and my brother would wade out into the ocean, and I would watch from the hut, never once venturing out into the water even though the days were mild and the ocean calm.

Many years before when I was a child, I went to the beach with my parents. We lived in Los Angeles then, and the beaches there are nothing like the beaches here in the Bay Area. The days were usually warm, if not hot, and the beaches were wide and inviting. You could watch the planes flying into LAX during the day and build a bonfire at night.

One summer day at the beach, my father took me out into the ocean. Hand in hand, we waded through each wave as the water crept up higher and higher until I was straining on tip-toe to feel the sandy bottom. Eventually I couldn’t reach the bottom any longer, yet we continued on as I wrapped my arms around my father’s neck. Finally, he too was treading the water as he led me to a small group of other swimmers. It felt like we were out in the middle of the ocean, the beach a distant line. I couldn’t comfort myself with the feeling of standing on my own legs and I couldn’t see the safety of the beach any longer. And I began to panic, grabbing my father’s neck so tightly that he couldn’t keep both of us afloat. I found myself underwater struggling to get my head back above it. As I broke through the surface I groaned and gasped for air, even though I couldn’t have been under water for more than a few seconds. The other swimmers nearby laughed as I cried and demanded that my father take me back to the beach.

To this day, I still have dreams of being submerged under water, and I still don’t go out into the ocean.

Each of us probably has some memorable experience of water—learning to swim, jumping off the high board, bubble baths and rubber ducks, water balloon fights and crossing the Golden Gate for the first time. Most of the time, water is a source of joy, refreshment, life, pleasure. Then other times, it kills and frightens. In these last two weeks, my nightmare of drowning became a reality for 150,000 people, and some of the poorest places on the planet were destroyed by the simple power of water.

This Sunday, we end our Christmas season in water. California is right now being blasted with the second major storm of the winter, and the liturgical calendar places Jesus in the middle of the Jordan river. The silent night of Christmas has become a tempest and the child in a manger is now a man on mission. Perhaps nature and the liturgical calendar are conspiring to teach us a deeper meaning of Christmas. As comforting as the nativity scene is, as safe as the beach feels, as warm as our beds are on blustery winter mornings, we can’t stay there. The Christ cannot remain a baby in our religious imaginations, we can no longer take for granted the force of water to change our world, and we cannot simply retreat back into our “usual” pre-Christmas routine as though the Incarnation had been just a “time out” from our normal lives.

This Sunday, we end our Christmas season in water. California is right now being blasted with the second major storm of the winter, and the liturgical calendar places Jesus in the middle of the Jordan river. The silent night of Christmas has become a tempest and the child in a manger is now a man on mission. Perhaps nature and the liturgical calendar are conspiring to teach us a deeper meaning of Christmas. As comforting as the nativity scene is, as safe as the beach feels, as warm as our beds are on blustery winter mornings, we can’t stay there. The Christ cannot remain a baby in our religious imaginations, we can no longer take for granted the force of water to change our world, and we cannot simply retreat back into our “usual” pre-Christmas routine as though the Incarnation had been just a “time out” from our normal lives.

The Christmas season, like the baptismal water into which we were drowned and out of which we were resurrected, is meant to change us and move us out into mission. Our gift-giving of the Christmas season now must become the daily sacrifice of love on behalf of those who are unloved. Our evergreens, dried out and discarded, must be transformed into a constant concern for the circle of all life and an appreciation for the resources of our planet. The candles and lights and holiday decorations that adorned our homes must become the mantle of joy and hope that now clothes our hearts throughout the year. And the wishes for peace sung in carols and proclaimed in Christmas cards now must become the hard work for justice in all our endeavors.

Ultimately Christmas is not for children. It is for the adults who have waded through the waters of tumultuous fear and uncertainty and yet still cling to hope, believing in the promise of peace, working for the dream of justice, and moving ever nearer to the reality of God’s reign.

In this week’s DSJ Liturgy Notes, you’ll find:

- Upcoming Events and Workshops

- Catechumenate Support Group – January 13

- Creating Sacred Space – January 13

- Cantor Workshop – January 25

- Vino & Vespers – January 28

- Liturgical Coordinators’ Gathering – February 1

- Diocesan 25th and 50th Wedding Anniversary Mass – February 5

- Rite of Election – 2005

- What Christmas Carols Teach

- Six Undervalued Carols

- Pope Paul VI Awards

- Finding God in Thailand

- Welcome to Sandra Pacheco!

- Classifieds: Seek and Ye Shall Find

Next time you dip your hand into the baptismal font, think of all the ways water has touched your life. And when you touch that holy water to your forehead, breast and shoulders in the sign of faith, recommit yourself to plunging fully into the joys, fears, hopes, and resurrections of daily life.

Diana Macalintal

Associate for Liturgy

FILED UNDER: OPENING ARTICLES

Monday, November 29, 2004

First Week of Advent

Waiting isn’t always easy. And I’m not talking about the “waiting for the copy machine to warm up” kind of waiting.

Waiting isn’t always easy. And I’m not talking about the “waiting for the copy machine to warm up” kind of waiting.

In college, my friend was tested for HIV, and we waited together a week for her results. During that week, we prayed and we talked about “what if.” She told me about her dreams, her fears, the people she cared about, the things she’s always wanted to do, and she confessed to me her regrets. That week, she began to see life differently, more clearly. All the things she had thought were important weren’t so important anymore. Slowly, the falseness was being stripped away, and what was left behind at the end of that week was a truer person—one who wanted to plunge into every moment of life, no matter what, instead of sleepwalk through it.